Being an Architect in a Firefighter Era

How Child Welfare Advocacy Fell Flat—and What Comes Next

Being an Architect in a Firefighter Era

How Child Welfare Advocacy Fell Flat—and What Comes Next

By Zach Laris, Founder & President

It took a Hill staffer’s blunt critique for me to see our field’s challenges and opportunities snap into focus.

It was 2022, and we were meeting over Zoom to talk about Title IV-B of the Social Security Act.

With its expiration date looming, the law should have generated natural momentum.

I’d been “in the room” to develop and pass several recent child welfare financing policies, including the 2018 Family First Prevention Services Act.

I thought reforming IV-B should have been simple.

Instead she cut me off before I’d finished my opening pitch:

“Look, I like you too much to waste both our time. You’re my fifth meeting on Title IV-B today, and this is the fifth set of unrelated ideas I’ve heard.

“Until your community can get on the same page and clearly communicate what it wants and why, you’ll be getting short-term extensions with no new money.”

That humbling moment sent me seeking answers to hard but clarifying questions.

You May Ask Yourself, How Did I Get Here?

In 2018, the field was at its peak– its ideas and alliances strong enough from years of collaboration and strategic leadership that it could move the Family First Prevention Services Act.

By 2022, we were struggling to build momentum for a straightforward reauthorization of a program as small as Title IV-B, which didn’t pass until early 2025.

Part of that story is the vacuum from losing key leaders.

But a new era is also demanding something different of our community than we’ve faced in recent memory.

Burning Down the House

Two threads are central to policymaking right now.

First is a high and persistent baseline volatility level.

You see it in partisan intractability, major restructuring across federal agencies, and the rising cost pressures and administrative burdens placed on states and localities.

The second is that policies designed for another era are failing to meet the challenges of this one.

Outdated policy structures create unanticipated incentives and accelerate drift.

You see it in Title IV-E’s outdated income-eligibility limits, which create drift, and in TANF’s structure, which shifts spending over time from direct economic assistance toward broader purposes.

Leaders across child and family policy, regardless of their politics or role, share some version of the sentiment that:

“it isn’t just the house that’s on fire… the whole neighborhood is on fire.”

When a single house is on fire, the instinct is to put out the flames and save what you can.

But when the whole neighborhood is burning, that instinct can prolong the pain and distract from choosing what to build next.

Throughout history we’ve had cycles of policy infrastructure that emerge, grow, strengthen, get stuck, decay, collapse, and lead to the next cycle.

We’re at that point of collapse now. It can feel like the end, but it’s the entryway into what comes next.

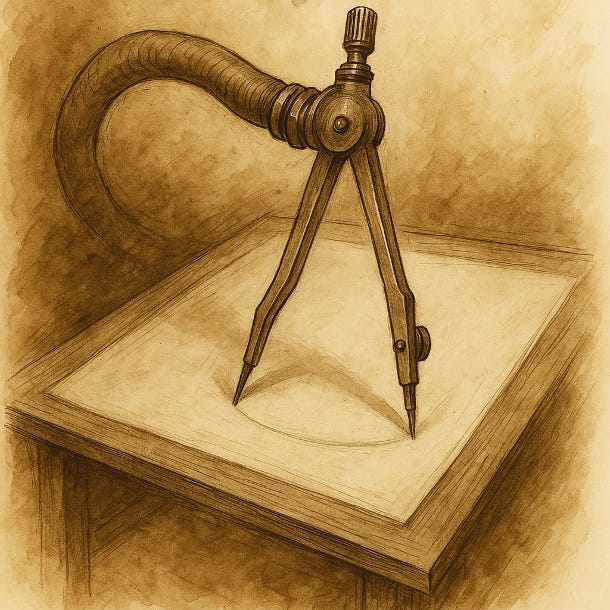

A moment like this invites the architect’s questions:

Is this what we would build if we were starting from scratch today?

Is this where we would build it if we could choose today?

Designing what comes next requires a position of real power and influence.

It will take an intentional shift in vision, and a return to these strategic principles that we’ve lost in recent years.

Scaling State Success

Good national ideas rarely originate in DC, and good state ideas rarely scale without national design; the architecture has to braid the two.

When I think back on my time as an advocate, nothing makes me shudder quite like recalling the outreach I did to state advocates and leaders.

Far too often, the point I reached out wasn’t when it was time to find what was working and build a policy idea, but when it was time to build momentum.

The ideas for what comes next won’t come from DC; they’ll be state and local successes worth scaling.

National and state advocacy and policy leaders and institutions can benefit tremendously from investing in relationships with each other, and infrastructure that makes this a default approach.

Creating Within Community

No single expert or organization can move a comprehensive agenda, and no coalition can succeed while leaving key players out.

It’s more effective to slow down and get into discussion with everyone else who has a stake in an issue. Including and especially those who don’t agree.

Longtime coalition leader MaryLee Allen regularly convened hundreds of advocates, policy experts, and stakeholders from all across the country for deliberative discussion, disagreement, and shared learning.

This created conversational space for those ideas to develop and garner support across the ideological spectrum, key preconditions for building something new.

Embracing Productive Adversity

When consensus becomes the cover charge at the door, the room reinforces blind spots instead of insight.

Policymakers often need to put out partisan proposals before they can negotiate across the aisle.

Advocates often need to issue a maximalist position before they can convey what they can live without.

That step isn’t annoying theatrics; it’s a core part of the process that creates the conditions for compromise that emerge from strong negotiating positions.

Family First is a great example of this. Two of its core policies emerged as partisan policy proposals from Senate Finance Committee leaders.

Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) and the late Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) put out expansive proposals on prevention and congregate care reform, respectively.

That gave them each a place from which to negotiate and make concessions as they found a viable version.

Consensus can be powerful, but only when it requires everyone actually giving something up after first pushing hard enough to generate friction.

We Know Where We’re Going

Progress depends on clarity, structural intelligence, and the ability to see across perspectives—not just within them. That’s what I founded Wonk to offer at scale.

As the policy structures we’ve all taken for granted unravel around us, our community faces an invitation to shape the next child and family policy framework.

What to build is debatable. Whether to build it is not.