Weekly Wonk: Signals Amid Shutdown

From the Founder’s Desk

Welcome, Wonks.

This week’s focus is on the infrastructure beneath child and family policy:

Data about infrastructure, for mental health treatment capacity; and

Data as infrastructure, with the latest updates to the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS).

We excerpt our latest premium Data Drop, finding that even as children’s mental health needs rose, the number of facilities serving Medicaid-enrolled kids fell in a third of states.

Our deep dive digs into the redesigned AFCARS system, showing that this isn’t just more data, but better data.

Both point to a central need; clear data that can drive decisions in child and family policy. That insight is what keeps leaders ahead of the next policy shock in a volatile era.

Speaking of volatility, the federal government remains shut down. Our Wonkatizer flags key personnel signals as talks remain at an impasse.

Stay sharp,

Z

From the Wonk Briefing Room

This Wonk Briefing Room snippet builds on our ongoing series digging into the data on children’s mental health.

We’ve looked at prevalence and treatment access, but what about treatment capacity?

Even as the data tell us that needs are rising, this analysis points to a concerning signal: a decrease of dedicated facilities for mental health that serve Medicaid-enrolled children.

And this is before the projected Medicaid spending reduction of nearly $1T over the next decade through the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

This Data Drop points to key tensions and pressures in financing policy that demand discussion.

If you want to read the full piece, sign up for our premium membership community, the Wonk Briefing Room, here.

Data Drop: Amid Worsening Child Mental Health, Treatment Capacity for Children on Medicaid Declined in One-Third of States

By Robin Ghertner, Director of Strategic Intelligence

Wonk readers know the headline: children’s mental health needs are rising, and the increase is steepest for kids in foster care. Previous Wonk analysis surfaced that trend.

We also know that children on Medicaid - including almost all kids in foster care - have seen over a 50 percent increase in mental health conditions from 2010 to 2019 (Cummings et al, 2025).

What has been less clear is whether treatment systems are keeping pace.

Research has long pointed to availability as the weak link (AACAP, 2024). Facilities are scarce, and many depend on Medicaid reimbursement to stay open.

Our analysis found that in 2023, over 90 percent of mental health facilities serving children accepted Medicaid.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act includes a projected one trillion dollar Medicaid spending reduction.

Depending on how states choose to respond to those cuts, and what financing ultimately looks like for facilities, even insured children could face shrinking options.

This raises a sharper question: as need rises amid financing pressures, what is the actual state of treatment access for children on Medicaid today — and which states are falling behind?

That’s the gap we set out to fill.

We went past prevalence data to ask whether treatment systems are keeping pace.

The results show where access is thin, where it’s eroding, and where looming policy shifts could quicken erosion.

The Treatment Landscape: Thin and Uneven

Nationally, there are less than two mental health facilities for every thousand kids on Medicaid who need care.

Our national treatment capacity estimate: 1.25 mental health facilities per 1,000 children on Medicaid with a diagnosed condition.

That national rate masks a stark divide. Only 11 states have over 2 facilities per 1,000.

Only Wyoming, Alaska, Utah, Nebraska, and Maine have over 3 facilities per 1,000. These also happen to be geographically big states, with smaller child populations.

At the bottom, 8 states have less than 1 facility per 1,000 kids on Medicaid with a condition, with Texas, Florida, and Georgia have the lowest, despite having some of the largest child populations in the country.

The signal is clear: most states are under-resourced, with children on Medicaid having limited access to needed treatment.

Weekly Wonk Deep Dive: New Policy Signals in New AFCARS Data

By Laura Radel, MPP, Senior Contributor

The Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) is the backbone of child welfare data, and is integral to our understanding of child welfare nationally.

But after more than 30 years in operation, the system was showing its age. With a recent upgrade–the most significant in its history–that is beginning to change.

Earlier this year, AFCARS’ long planned redesign finally went online–data from Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 was released in May, and FY 2024 in September.

The new AFCARS Dashboard finally brings research-level detail into public view. No downloads, no coding—just tables that reveal how children move through the system.

As we’ll show, the redesign doesn’t just expand data, it expands what we can see.

It surfaces new signals about how policy choices are shaping children’s experiences in care, revealing where systems succeed, stall, or slip.

The AFCARS Dashboard: What’s New and Why It Matters

The AFCARS Dashboard raises the standard for publicly available child welfare data.

The new Dashboard exposes dimensions that were buried or blurred in the old system: demographic patterns, permanency plans, and living arrangements can now be broken down by both counts and rates, allowing true cross-state comparison.

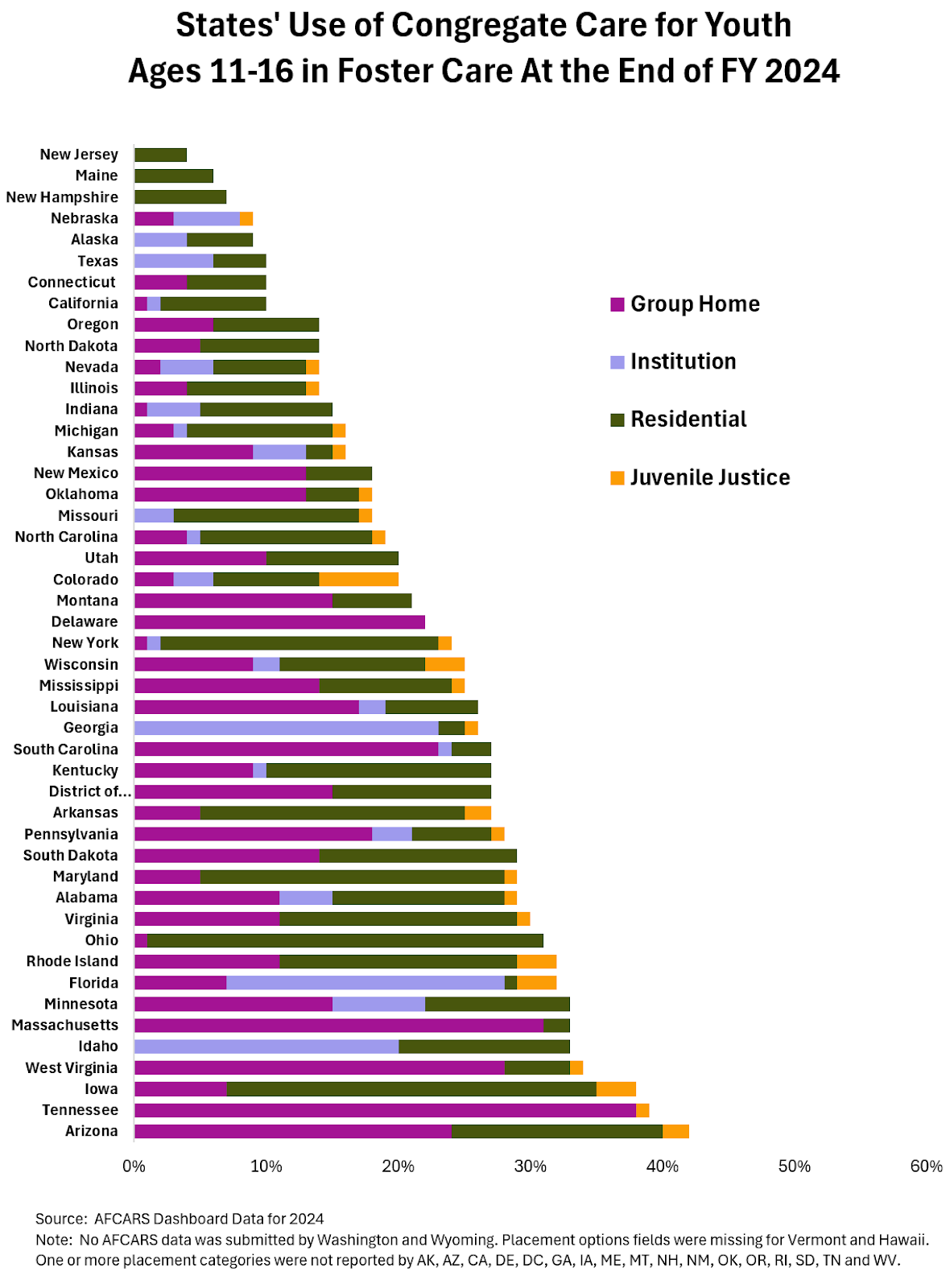

As an example of what is now available, the chart below uses data from the dashboard to illustrate states’ varying use of congregate care placements for youth ages 11 to 16, from as low as 4 percent in New Jersey, to as high as 42 percent in Arizona).

In addition, for many categories of information, data are presented both by counts and by rates, making cross-state comparisons easier.

Critically, data are generally available for three populations of children:

Children entering foster care;

Children currently in foster care; and

Children who exited foster care.

This enables researchers, policymakers, and advocates to see, for instance, how placements, permanency goals, and living arrangements evolve over time—not just where they end up.

Updated placement types.

Placement types have been updated to reflect current child welfare setting types, such as treatment foster care and shelter care, which could not previously be identified.

Kin licensure status.

For the first time, AFCARS identifies whether relatives are licensed or unlicensed, exposing which states rely heavily on unlicensed (usually unpaid or lower paid) relative care.

More nuanced adoption counts.

AFCARS now distinguishes between children who have an adoption permanency plan and those who are legally free for adoption.

These data can be used to explore, for instance, how often each state creates legal orphans who later age out without achieving permanency.

Together, these upgrades move AFCARS towards decision intelligence for child welfare leaders across the country.

State leaders can benchmark themselves against peers; federal watchers can track how policy shifts show up in real numbers; and advocates finally have a public window into patterns that used to live only in raw datasets.

Coming Attractions: The Next Wave of Insights

The AFCARS Dashboard upgrade is a major leap, but it’s only the start.

As states get better at reporting new data elements, AFCARS will expose what’s working, what’s not, and where policy change could have the greatest payoff.

For leaders, that shift is catalytic: it creates the ability to spot structural inequities, test whether reforms are working, and pressure-test policies that have long run on assumptions instead of proof.

Sharper insights on the following topics should be available in the coming years:

Children’s trajectories in care.

The revised system includes longitudinal reporting of children’s full placement histories.

In the past only a current placement setting was reported along with a count of total placements the child had experienced.

This will create a new pressure point for states with high placement churn—and a tool to test whether family placement reforms are actually sticking.

Adopted children.

For the first time, adopted children stay visible in AFCARS as long as their agreements remain active.

This opens a policy signal on system balance: how much the system is weighted toward adoption subsidies versus children currently in foster care.

Sibling groups.

AFCARS 2020 will record whether a child in foster care has siblings, whether those siblings are also in foster care, and whether they are in the same foster home as the focal child.

For state leaders, this adds an accountability metric where one didn’t exist before: how well systems preserve sibling bonds that policy claims to prioritize.

Interjurisdictional placements.

We’ll know whether the child is placed outside the child welfare agency’s service area, and how far away they are.

The new data will make clear for leaders which states rely most heavily on out-of-state placements.

Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA).

With a new ICWA indicator, we will be able to better understand the experiences of American Indian and Alaska Native children.

These data will demonstrate how frequently courts determine ICWA applies to Indian children and how outcomes differ for those children.

Expect heightened scrutiny of compliance and consistency—and a new source of data-driven accountability for state courts and agencies alike.

Interagency custody transfers.

For the first time, AFCARS will specify whether a discharge to another agency indicates another state or tribal IV-E agency, a juvenile justice agency, or a mental health agency, each of which has different implications for children.

That visibility surfaces a hard systems signal: when children are exiting care on paper but not in practice.

Educational attainment.

New fields on school enrollment, grade level, and special education status allow improved attention to the educational needs of children in foster care.

Some Limitations

HHS cautions that the latest AFCARS data will not be directly comparable to earlier years because the reporting populations and field definitions have changed.

In addition, two states did not submit AFCARS data in either 2023 or 2024 (Washington and Wyoming), and they flagged data quality issues.

Other states omit selected variables and the quality of reporting varies, particularly on new data elements.

That’s normal turbulence for a system rebuild. Data quality will improve as states gain experience.

What Comes Next

The bottom line is that the new AFCARS isn’t just a data upgrade–it’s a policy accelerator.

Over time, this dataset will do more than inform reports—it will shift the questions agencies ask, the indicators legislatures monitor, and the leverage points reformers target.

For child welfare systems long defined by compliance reporting, AFCARS 2020 marks the start of an evidence era that will be impossible to ignore.

Wonkatizer

HHS Layoffs Begin Amid Shutdown

The Move

As the shutdown persists, the Trump Administration has begun mass Reduction-in-Force (RIF) actions , with significant impact on HHS.

A court filing confirms 1,100–1,200 job cuts at the Department of Health and Human Services, part of more than 4,000 positions slated for elimination across federal agencies.

The Context

Layoff notices have gone out to staff in HHS, Treasury, and Education.

Federal employee unions have sued, arguing the administration cannot conduct permanent layoffs while agencies are unfunded.

Why It Matters

HHS oversees core safety net programs—Medicaid, TANF, and child welfare funding streams that depend on steady administrative oversight.

A staffing contraction during a shutdown increases the risk of delayed reimbursements, regulatory backlogs, and slowed program guidance to states.

Watch For

Court rulings on RIF legality, additional detail from HHS on which offices are affected, and any Congressional response if service or payment disruptions surface.

Alex Adams Confirmed to ACF

The Move

The Senate has confirmed Alex Adams as Assistant Secretary for Family Support at the Department of Health and Human Services, overseeing the Administration for Children and Families (ACF).

The role gives Adams authority over major human services programs, including TANF, child welfare, and Head Start.

The Timing

His confirmation fills a post that’s been filled on an acting basis since January. Typically that would bring steady certainty and a defined agenda to the agency’s work.

A curveball here is the ongoing and uncertain disruptions during the shutdown, on top of major ACF reorganization and staffing cuts earlier this year

Why It Matters

Adams brings a fiscal lens to his public service roles; in Idaho his leadership was central to the state’s improved bond rating.

His human services leadership in Idaho focused on extended foster care, expanded services to address family crises, and promoting family-based placements.

Watch For

As a new political leader, his early communications and actions will be the early signals to parse for a sense of direction and priority.

His confirmation hearing pointed to a clear focus on child welfare. A key question will be how much leeway Assistant Secretary Adams has to chart his own agenda.