Weekly Wonk: Early Fireworks

Medicaid debates, plus our first original research piece

Happy 4th of July Week, Wonks.

We’ve got lots to share, and it’s not even all about budget reconciliation; we’ve got our first Wonk Data Drop original research, on pediatric psychotropic medication use.

Partners Making Your Weekly Wonk Possible

Let’s get right to it.

Early Fireworks Accompany Senate Reconciliation Votes

President Trump and Congressional Republican leaders continue to call for enactment of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act by July 4th. The fireworks are already here.

The 940-page bill cleared a key procedural hurdle on June 28th, passing 51-49.

Senators Rand Paul (R-KY) and Thom Tillis (R-NC) opposed the procedural vote, over the bill’s deficit impact and Medicaid cuts, respectively.

The Early Fireworks

Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC), fresh off announcing his retirement, described the bill’s Medicaid impact as “betraying” President Trump’s campaign promises on Medicaid.

He also shared in public remarks that he told the president the bill:

“will hurt people who are eligible and qualified for Medicaid”.

Senator Tillis’ opposition emerged in response to the bill’s structural changes to Medicaid, including limits on provider taxes and other flexible financing tools.

He has raised concerns about the bill’s impact on rural hospitals, and the 663,000 North Carolinians who could lose coverage if it’s enacted.

The bill is now going through reconciliation's vote-a-rama; seemingly interminable votes on non-binding amendments; expect many on Medicaid.

Clearing the procedural vote does not guarantee Senate passage.

Senate GOP leaders negotiated an array of amendments to secure that vote, including timing tweaks for Medicaid financing rule changes.

On June 29, the Senate parliamentarian rejected a carefully crafted provision boosting Medicaid payments to Alaska and Hawaii.

That key change was meant to earn support from Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), who has expressed significant concern about the bill’s cuts to safety net programs.

What Comes Next

Expect a long vote-a-rama full of contentious amendments, including Senator Rick Scott’s (R-FL), which would reduce federal funding to states with expanded Medicaid.

Senators Paul and Tillis remain likely “no” votes on final passage.

Senate passage, still not a given, also does not make House passage inevitable.

The Senate bill has generated House Republican opposition over its differences from what the House passed; it both adds more to the deficit and cuts more from Medicaid.

If this week’s ambitious deadline slips, passage is still possible.

The real timing driver to watch remains the debt limit, which the bill lifts.

That could let negotiations stretch into August.

Wonk Data Drop

Data drives Child Welfare Wonk. From the beginning we’ve brought you original data analyses that cut through the noise to surface what matters.

Now we’re scaling that effort; inviting sharp researchers to drop new data-driven insights you won’t find anywhere else.

These fast, focused analyses are made for decision makers; rigorous, fluff-free, and aimed at the underlying structural tensions that actually matter in policy decisions.

Children in poverty and on Medicaid are more likely to use psychotropic medication, with gaps between medication use and diagnosis

By Meredith Dost, PhD and Robin Ghertner, MPP

BLUF

Psychotropic medications are being used by millions of children in the U.S.

But gaps between diagnosis and treatment suggest systemic misalignment: many kids are medicated without a diagnosis, while many with diagnoses aren’t receiving medication at all.

Our analysis indicates that utilization patterns are higher among children in poverty and on Medicaid, raising questions about access and quality in pediatric mental and behavioral healthcare.

Nearly 9% of all children took psychotropic medications in 2021-2022.

11% of all children had a mental or behavioral health diagnosis.

3 in 10 children using psychotropics did not have a formal mental or behavioral health diagnosis.

More than 4 in 10 children with a diagnosis were not taking psychotropics.

Children were more likely to use psychotropic drugs if they were in poverty or on Medicaid, despite being no more likely to have a relevant diagnosis than their counterparts.

Why Psychotropics Matter for Policies Affecting Children

The recent Make America Healthy Again Commission report raised broad concerns about prescribing psychotropics - also called psychiatric medication - to children.

Long before that, there has been an ongoing policy and practice debate about these medications in child welfare and children’s behavioral health.

The evidence on the effectiveness of psychotropic medications on children is limited.1 In particular, observers have raised concerns about the inappropriate or over prescribing of medications to children.2

Understanding who gets these medications and whether they have a relevant diagnosis can inform policy discussions about oversight and access to both these medications and other treatments children may need.

What’s Missing in the Psychotropic Medication Debate; data on current trends.

Any effective policy deliberation needs grounding in facts.

We know psychotropic prescribing increased in the early 2000s.3 A recent study found nearly 28% of children in foster care were prescribed at least one psychotropic medication.4

We also know that low-income children are 2-3 times more likely to have mental health problems.5

In this analysis we provide insight into current national trends to help decision-makers decipher what’s going on:

How broadly are psychotropics currently used in the population of children nationally?

How many children with and without related behavioral health conditions are using these medicines?

Are there differences across family income and Medicaid receipt?

Approach

To answer these questions we use a nationally-representative survey commissioned by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services called the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), for years 2021-2022 (latest available).

The MEPS surveys families and individuals along with their medical providers and employers to provide in-depth data on the cost and use of health care in the U.S.

What the Data Tell Us

Nationally, almost 9% of all American children received a prescription for at least one psychotropic medication.

11% of children were diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition in 2021-2022.

Looking more closely at the relationship between diagnosis and medication (see Table 1), the data reveal a significant disconnect:

Nearly 70 percent of children using psychotropic medications had a diagnosed mental or behavioral health condition.

That means that about 30 percent of children using these drugs did not have a formal diagnosis.

This calls into question whether these medications are being appropriately prescribed, and whether they are prescribed to manage behavior in lieu of clinical care or other interventions.

More than half (56 percent) of children diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition took at least one psychotropic medication.

That means that over 40% of children with a condition were not taking psychotropics.

Table 16 presents national estimates of the prevalence of psychotropic medication use and mental or behavioral health diagnoses, as well as how medication use and diagnoses relate to each other.

Children in poverty were more likely to use psychotropic medication than those not in poverty.

Similarly, children on Medicaid were more likely than children not on Medicaid to use these medications.

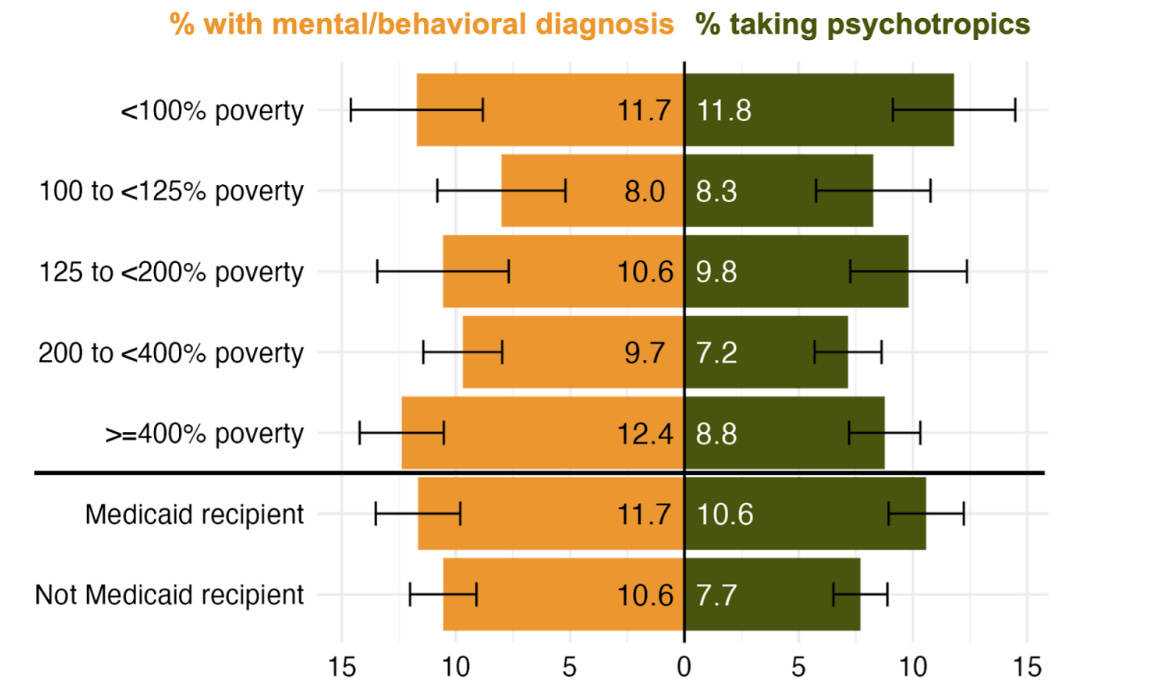

Figure 1 presents the prevalence of child psychotropic medication use and related diagnoses by subgroups of the population, focusing on poverty status and Medicaid receipt.

11.8% of children in poverty (with family incomes up to 100% of the Federal Poverty Level) used psychotropics, the highest across income groups. As a comparison, 7.2% of children with family income between 200 and 400% of poverty used psychotropics.

10.6% of children receiving Medicaid used psychotropics, compared to 7.7% of non-recipients.

At the same time, kids in poverty or on Medicaid were not more likely to be diagnosed with a mental or behavioral health condition compared with other children.

Even though there are differences shown in the figure, the differences are not statistically significant - the black lines show overlapping confidence intervals.

We can’t say for certain that the differences are meaningful.

Figure 1.7 Children in poverty and on Medicaid were more likely to use psychotropic medication but not more likely to have a mental health diagnosis

Child Psychotropic Use and Mental Health Diagnosis by Family Income as % of Federal Poverty Level and Medicaid receipt

Why are children in poverty and Medicaid more likely to use psychotropic medications?

It’s possible children in poverty and on Medicaid may be more likely to use these drugs because other therapies are unavailable or unaffordable.

There are other factors involved, such as difficulties in coordinating care and collaborating across systems - particularly foster care systems.

MEPS data can’t reveal much about these different factors, so we have to look to other data sources to uncover the reasons.

Over or Under-Utilization?

This analysis doesn’t give a definitive answer; our suspicion is that it is mixed.

3 in 10 kids using them don’t have a diagnosis, which points to a possible problem in too much or inappropriate prescribing.

But not all kids with a diagnosis use medication. Some may be getting an alternative therapy, but some may be receiving no treatment.

One-size-fits-all is rarely an effective policy approach. As policymakers in behavioral health and child welfare think about addressing psychotropics, they need to consider the different aspects of the issue.

Children without access to effective, alternative therapies could be left with no treatment if access to psychotropic medication is limited. Research is unclear on the later consequences of psychotropic use relative to no treatment at all.

The likely concurrent over-prescribing of psychotropics and limited access to effective mental and behavioral health treatment points to a balancing act that policymakers face to avoid exacerbating the issue in either direction.

So what about differences among other subgroups of children?

In a follow-on analysis, we will explore differences in prescribing and diagnosis by racial and ethnic groups as well as the interaction between race and poverty.

Meredith Dost is the National Poverty Fellow at the Institute for Research on Poverty at UW-Madison. This work does not represent the views of the university.

Robin Ghertner is Child Welfare Wonk’s Founding Director of Strategic Policy Intelligence.1

Grants.Gov Gets Out of the DOGE-House

Following months of uncertainty, federal agencies are regaining control over the grantmaking process.

Role of Grants.gov

Overseen by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Grants.gov is the key federal portal for soliciting applications for $500B+ in federal funds.

Shift to DOGE

DOGE became platform administrator this spring, centralizing review of every funding opportunity.

The result? Dozens of delayed grants and questions over the rules for grant decisions; everything from support for Alzheimer's caregivers to child and family programs.

This also happened in the context of the “Defend the Spend” initiative, which further delayed disbursement of funds for federal programs.

DOGE Denied

Now DOGE’s central gatekeeping role is out.

Agencies can post NOFOs directly — though political appointee sign-off requirements remain.

This shift follows changes in the role and influence of Elon Musk and DOGE.

It also occurs amidst contested legal questions about whether federal agencies must spend funds Congress appropriates.

Rerouting Red Tape

White House officials say DOGE still plays a “facilitator” role, with embedded staff at each agency.

It’s not yet clear whether the change will lead to revisiting delays and expirations of impacted grants.

The key question now is if decisional authority reverts to agency officials, or their DOGE teams.

Happy 4th of July

Enjoy the holiday; we look forward to sharing more strategic intel when you’re back.

McLaren, J. L., Barnett ,Erin R., Concepcion Zayas ,Milangel T., Lichtenstein ,Jonathan, Acquilano ,Stephanie C., Schwartz ,Lisa M., Woloshin ,Steven, & and Drake, R. E. (2018). Psychotropic medications for highly vulnerable children. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 19(6), 547–560.

Theall, L., Ninan, A., and M. Currie (2024). “Findings from an expert focus group on psychotropic medication deprescribing practices for children and youth with complex needs.” Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 3.

Crystal, S., Mackie, T., Fenton, M.C., Amin, S., Neese-Todd, S., Olfson, M., and S. Bilder (2016). “Rapid Growth of Antipsychotic Prescriptions for Children Who Are Publicly Insured Has Ceased, But Concerns Remain.” Health Affairs 35:6, 974–982.

McLeigh, J.D., Malthaner, L.Q., Tovar, M.C. and M. Khan (2023). “Mental Health Disorders and Psychotropic Medication: Prevalence and Related Characteristics Among Individuals in Foster Care.” Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 16, 745–757.

Kirkbride JB, Anglin DM, Colman I, Dykxhoorn J, Jones PB, Patalay P, Pitman A, Soneson E, Steare T, Wright T, Griffiths SL. The social determinants of mental health and disorder: evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry. 2024 Feb;23(1):58-90.

Notes: Weighted tabulations shown. Unweighted total N=9,887. Relevant health conditions include mental or behavioral health diagnoses.

Data source: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 2021-2022. Full-year consolidated files merged with prescription drug and medical condition components for each year, then pooled.

Notes: Black bars are 95% confidence intervals. Weighted tabulations shown. Unweighted total N=9,887. Data source: MEPS 2021-2022.